Much has been spoken about the failure of the December 2021 release 83, directed by Kabir Khan, at the box office. Analysts have offered various explanations, such as the film’s documentary-style narrative, impact of the third wave of the pandemic, ineffective marketing, etc. While there could be some truth in at least some of these theories, a factor that has been rarely spoken or written about is the excessive use of English language in the film, and how it curtailed the film’s box office potential.

Among those who watched the film in theatres, the response has generally been positive. The film scored 69 on Ormax Power Rating (OPR), a fairly high number that indicates that the film was ‘loved’ by its audience. But these audience largely came from the high-end multiplexes of the big cities. What about the audience in the mini metros and the smaller towns, and the single screens? The advocacy is far more mixed there, even negative. And many of them simply rejected the film at the marketing stage itself. In this analysis, we offer a three-word explanation to explain why the film did not achieve more at the box office: Too much English.

We watched the film on streaming closely to see if our initial perceptions that the film has too much English for its own good were true. Here’s what we found.

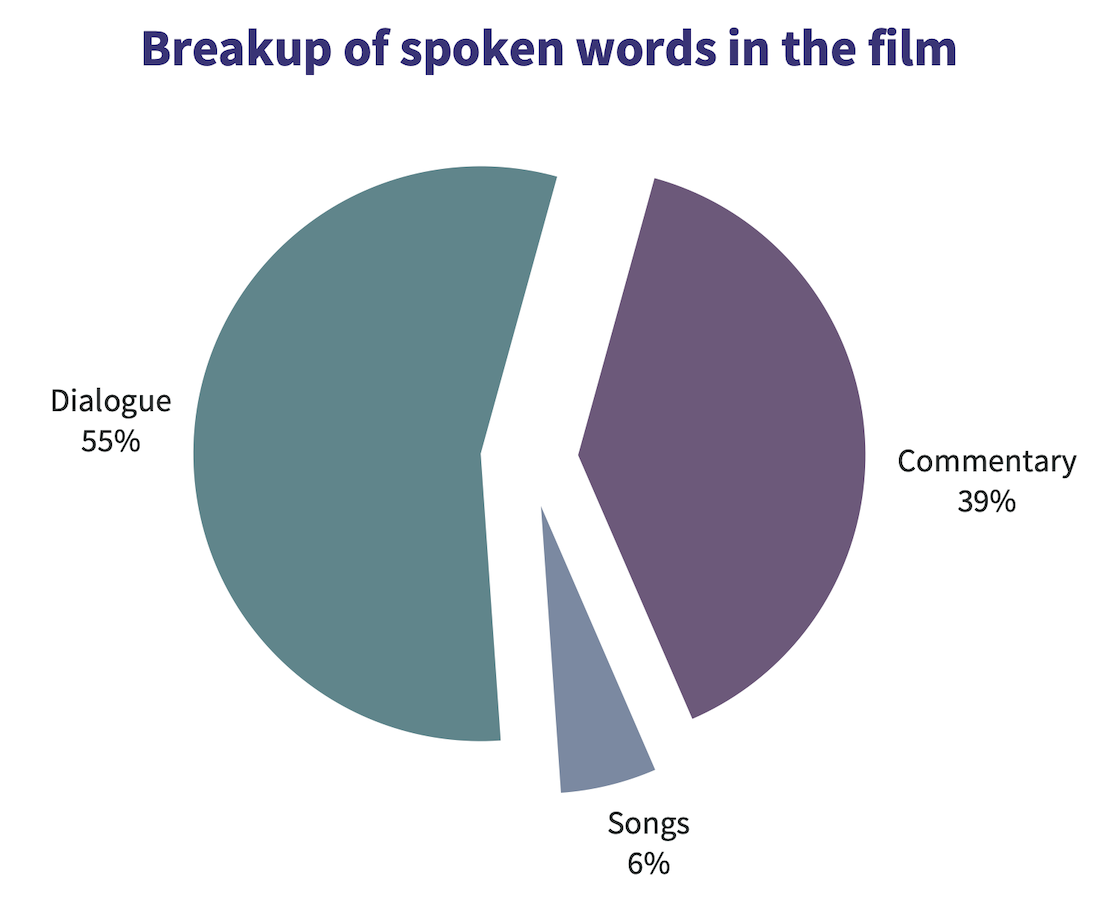

The film (the Hindi version) has a total of 12,316 spoken words. These can be divided into three types: Dialogue, Commentary and Songs. As can be seen in the chart below, Commentary comprises of a significant portion of the film, accounting for as many as 39% of the spoken words. If you have watched the film, you will not find this high percentage surprising. After all, about 45% of the film’s 157 mins. runtime (excluding credit rolls) is consumed in the coverage of the various cricket matches India played in the 1983 World Cup.

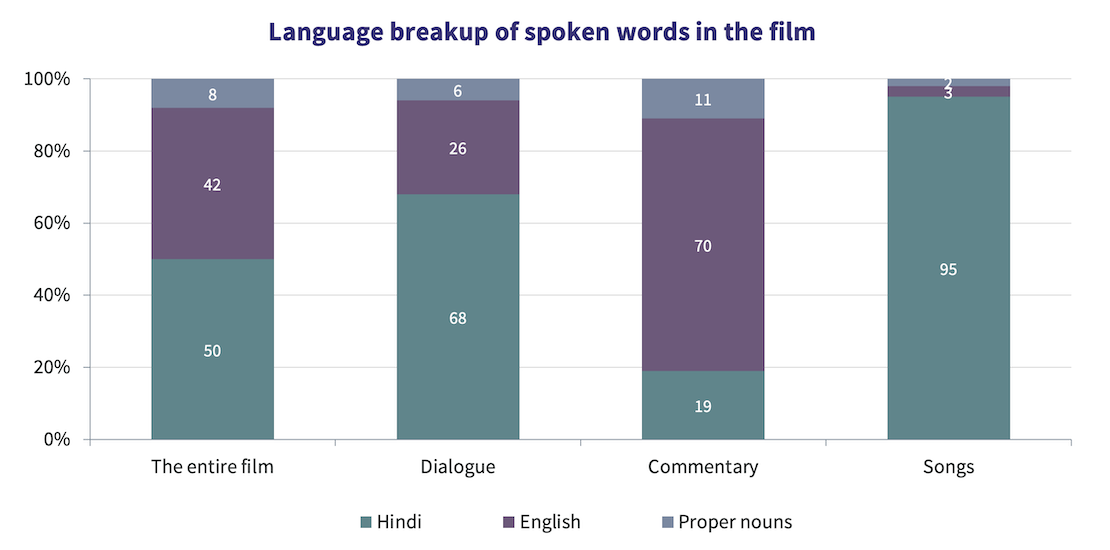

But it’s the chart below where our real story lies. We classified these 12,316 words into four types, based on their language: Hindi, English, Other languages & Proper nouns (typically, cricketer names). ‘Other languages’ contributed only 0.3% to the total number of spoken words, and hence, have been removed from the chart. The results are revelatory, even shocking.

The ‘Hindi’ film 83 is actually a bilingual film, with 42% of its spoken words being in the English language! This proportion goes up to 45% if we exclude proper nouns, and further to 48% if we exclude the songs, which use predominantly Hindi lyrics.

The main ‘culprit’, if we can use that word, is the maker’s choice of using English as the predominant language of commentary (enacted by Boman Irani and Farokh Engineer), perhaps to be authentic to the actual event, where Hindi television commentary was available only in the knock-out matches (Hindi radio commentary in the group matches is used in the film, but very sparingly). While the intention is understood, the outcome has turned out to be severely limiting for the film’s box office prospects. A film that’s relying so heavily on English instantly alienates a large section of the audience, not just in the single screens but even in the multiplexes in mini metros and small towns. Even Hollywood films are available in language dubs today, to make them more accessible to the larger audience. 83’s decision to use English as the primary language of commentary is a step in the other direction: It made the film inaccessible to many.

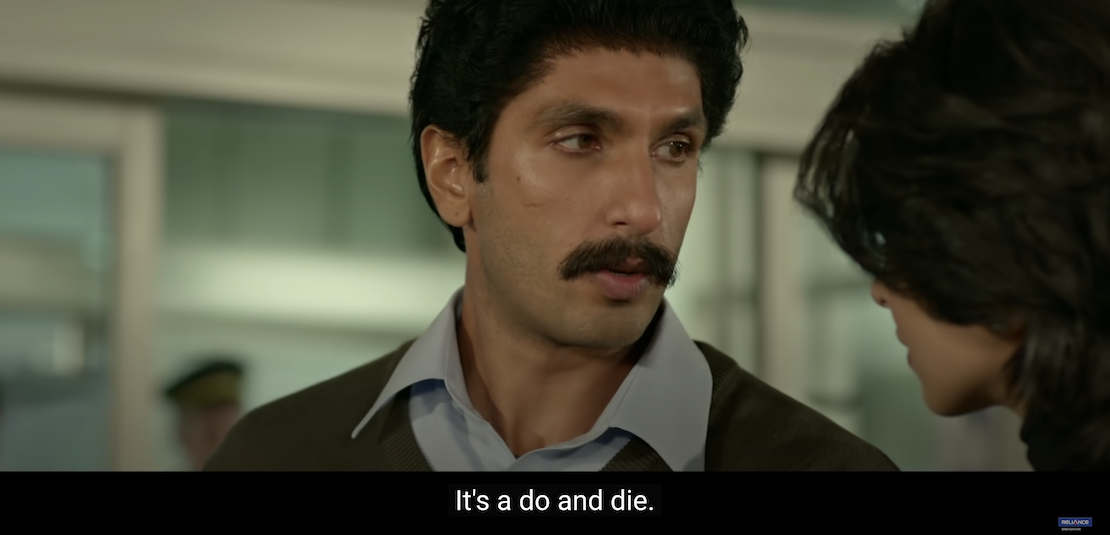

The problem continues with the way the film uses language-based punchlines to evoke humour. Many of these jokes require a rather sophisticated understanding of the English language. Most Indians who can comprehend English (and that’s a small section to begin with) barely have a functional understanding of the language. 83 misses this reality check. For example, the ‘Acidity vs. STD’ joke relies on a certain minimum familiarity with the English language, and the ‘Do and Die’ joke assumes familiarity with an English language phrase (Do or Die).

Even otherwise, Kapil Dev’s discomfort with the English language is the source of recurring attempts to tickle the audience’s funny bone. It’s ironical that a large section of the film’s target audience won’t get these jokes, because their own spoken English is at a similar level. And it didn’t help matters that the film’s main trailer relied extensively on such jokes and punchlines to entice the target audience to buy a ticket.

Clearly then, 83 is a well-meaning film that put its pursuit of authenticity ahead of its endeavour to be inclusive and accessible. It’s difficult to say whether the makers, including the director Kabir Khan, over-estimated their audience’s familiarity with the English language, or whether they consciously chose to alienate them.

It’s the elitist, big-city gaze perhaps. Most content creators based out of Mumbai, across theatrical, streaming and television categories, tend to over-estimate their audience’s understanding of the English language. It’s a rampant problem that’s impacting a large volume of Hindi content being produced today. Over the last 14 years of our work, we have met very few creative or business decision-makers who understand the degree of this dysfunctionality between the audience and the creators.

English is an aspirational language in India, indeed. But it’s not a language of cultural expression, beyond a miniscule minority of metropolitan audience. The business impact of over-stuffing Hindi content with English dialogue is real. And filmmaking (and content creation in general) is too expensive a business to not factor for this impact.

Urban romcoms: The Delhi NCR story

An analysis of why Delhi NCR contributes disproportionately to the box office of urban Hindi romcoms

The Ormax Box Office Report: 2025

Powered by Hindi cinema’s strong comeback, 2025 became the biggest year ever at the Indian box office, with gross collections of ₹13,395 Cr, even as footfalls stayed flat

Introducing Ormax Media Affluence (OMA)

OMA is a new audience classification system designed specifically to measure affluence level of audiences in context of the media & entertainment sector in India

Subscribe to stay updated with our latest insights

We use cookies to improve your experience on this site. To find out more, read our Privacy Policy